The Odyssey of Robert Crumb: From Counterculture King to Cash Cow

In 1968, when Robert Crumb launched Head Comix, poet Allen Ginsberg aptly dubbed him the “supreme funny underground comic strip incarnation of the post-historic flower age.” Crumb, a connoisseur of LSD, managed to evoke a trip without anyone needing to pop a tab—they could just read his chaotic illustrations instead. It’s said that countless businesses swiped his art, while Andy Warhol probably watched from above, green with envy, only to kick the bucket before Crumb’s commercial success kicked in.

Breaking Taboos and Family Drama

In the biography Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life by Dan Nadel, we come face-to-face with the brazen taboos that Crumb’s work smashed like a piñata at a toddler’s birthday party. Critics have entreated bloody sacrifices of Crumb for his unabashed sexism and racism, while he casually strolled away, gaze fixed on his next satirical masterpiece. Born in 1943, young Robert lived in a family gothic enough to make Tim Burton blush—featuring a no-nonsense Marine father and a Catholic mother who had a child with a stepbrother before tying the knot. Talk about family reunions!

Details like the moment when Robert and his equally troubled brother, Charles, ditched the Catholic Church for good and Crumb’s first museum show in Peoria, Illinois, are peppered throughout Nadel’s narrative. It’s noteworthy that Crumb attempted to awaken the Peoria locals with a proclamation that simply shouted, “My drawings are my personal attack on the absurd world we live in!” You know you’ve made it big when your art is described as an “attack,” rather than just another set of doodles in a dusty attic.

Wholesome Beginnings to Dark Tales

Skipping art school was Crumb’s first wise move; instead, he found himself at American Greetings, mastering the fine art of looking wholesome while plotting his next dark narrative, much like an undercover agent in a children’s cartoon. His satirical lens captured characters that would make Norman Rockwell rise from his grave, including over-the-top Middle American types and a guru named Mr. Natural. Crumb admitted that his work reflected an “inner hell,” but hey, who hasn’t wished to illustrate a little bit of chaos now and then? Unlike Andy Warhol’s blase soup can, Crumb packed a punch that hit you right in the gut.

The Crumb Canon: What Got Us Here

By early 1966, Nadel observes that Crumb had assembled the very language to convey his simmering thoughts on life, love, race, and civilization. His creations—from the ‘Keep On Truckin’’ images to Fritz the Cat—were not just hits; they were cultural earmarks. Still, the irony wasn’t lost on him. His comics often landed in the hands of those distributing smut under titles like “Fug” and “Snatch.” Perhaps moralists had a point? The lawyers suing various enterprises that “borrowed” his art proved critical for his survival, but context is everything, right?

Living Through the Sexual Revolution

Crumb thrived during the sexual revolution, navigating relationships that would make any marriage counselor gasp. His honesty came with a side of controversy, rendering him a target for critiques. Nadel notes that Crumb wasn’t merely observing society; he was very much a part of it, contributing his quirks and yet wrestling with his internal conflicts. In what might qualify as the ultimate existential crisis, it turns out he was often appalled by his own creations.

From Paris with Love—Or Is It Fear?

Fast forward to the 1980s, when Crumb relocated to France, perhaps hoping that a language barrier would provide the social distance he desperately needed. The French, famous for their sophisticated tastes, ironically idolized him. Settling in Sauve—echoing the French term for “save”—Crumb found a slice of solace. Yet, if you ask him, an American deep down, that slice might still taste like home.

Art and Commerce: The Late Bloom

After years of bartering his art for vinyl records, Crumb hit a jackpot of sorts when the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art shelled out $2.9 million for original drawings from The Book of Genesis Illustrated by R. Crumb. To his shock, this piece became a smashing success, making him a hot topic in both art circles and family dinners. Nadel points out that this might be Robert’s ultimate fusion of his eclectic sensibilities onto the canvas of Western civilization. Yet, can we really call him a Surrealist?

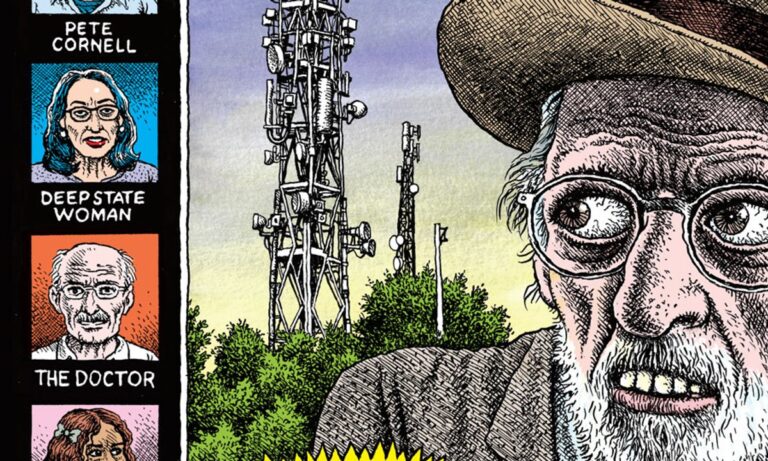

In a world where the lines between artist and character blur, Crumb keeps us guessing. As he returns to the comic scene with a feverish self-portrait that mocks grand conspiracies—his work has certainly evolved, but how much of that is real and how much is a theatrical charade? Looks like the audience will have to determine which Crumb is speaking: the artist or the persona, or perhaps they are one and the same after all.