The Birth of Motion Picture History: Lumière Edition

Ah, Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory—the film that supposedly invented cinema, brought to us by those dashing pioneers, the Lumière Brothers. One can only imagine the brothers’ mother watching their work and thinking, “Finally, something more exciting than my knitting!” As history tells us, the Lumières turned the mundane act of workers leaving a factory into an artistic triumph, forever changing the trajectory of film. In a twist of fate, not long after, the visionary Mitchell and Kenyon thought, “What if we do that, but with more lace and far less French flair?” Spoiler alert: they nailed it right in the industrial heart of England.

Mitchell and Kenyon’s Industrial Masterpiece

Enter Workers Leaving Thomas Adams Factory, circa 1900. This little gem features hundreds of lace workers sauntering out of a Nottingham factory as if they were on a red carpet—just without the paparazzi and questionable fashion choices. Who knew leaving work could look so… cinematic? But it wasn’t just a one-hit wonder; the film-follow-up whipped up a delightful montage of workers strutting through the streets, gazing up at the camera as if it were an alien spacecraft. Clearly, every lunch break is a potential Oscar-worthy moment in Nottingham’s industrial landscape.

Silent Cinema and the Working-Class Narrative

The representation of working-class life in Nottingham took center stage in the early 1900s, mostly because there weren’t any other blockbuster hits at the time. Aside from the odd silent short like Tram Rides through Nottingham, which featured an Edwardian tram fighting its way through the chaos of city life, the cinematic world was a bit of a snooze-fest. Then there’s the riveting Scenes on the Trent, showcasing a boat filled with Passengers who—let’s be honest—probably should have taken the tram instead. Nottingham’s on-screen action was limited to people doing… you guessed it, daily life things. Meanwhile, J.H. Poyser and his Co-operative Film Club were recording the essence of small-town existence, achieving what can only be described as the cinematic dream of filming children’s outings. But really, what screams ‘cinematic gold’ more than a newsreel of kids in 1936?

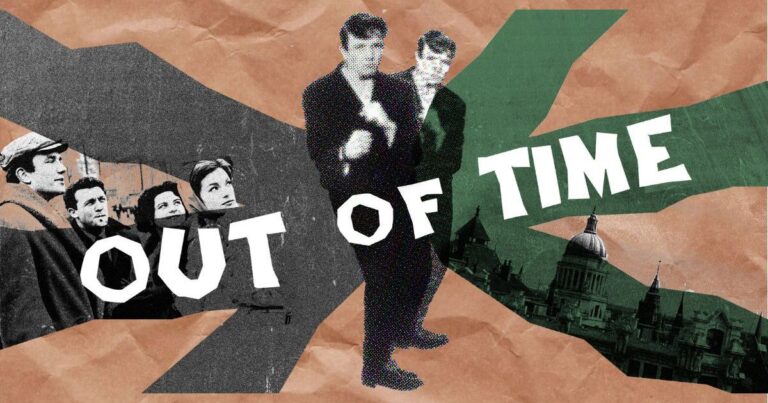

Revolutionizing Cinema: British New Wave

Fast forward to the postwar era, and suddenly British cinema got a makeover—think less lace factory and more existential dread. Enter the British New Wave, where directors like Lindsay Anderson and Karel Reisz adapted kitchen-sink dramas, because, you know, who doesn’t love a good plumbing metaphor? This new wave brought us the “angry young men,” forever scowling and expressing dissatisfaction with life—as if anyone in the audience was having a great time, either. These films dabbled in a slightly more glamorous version of film noir, highlighting the riveting life of postwar working-class folks while drenching scenes in shadows, perhaps to save on lighting costs.

Saturday Night and Sunday Morning: A Nottingham Classic

Among these cinematic journeys of despondency stands the iconic Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. This is the star-studded tale of an angry factory worker who really, really looks forward to the weekend. Talk about relatable content! This sweet ode to Nottingham’s wild nightlife (which mostly consisted of factory workers and, we can only assume, an awful lot of beer) earned a BAFTA—because who wouldn’t want to celebrate the charm of a city where the best night out involves counting the hours until Monday?

From Industrial Life to High-Brow Art: A Journey Worth Watching

So there you have it, folks! From the Lumière Brothers, whose film sparked a revolution more thrilling than watching paint dry, to Mitchell and Kenyon’s lace-adorned operas, and eventually into the gritty recesses of British New Wave, we’ve journeyed through the expansive landscape of Nottingham’s working-class representation. Who would have thought that lazy Sundays could conjure such a rich tapestry of cinema filled with people both visually riveting and utterly ordinary? Hollywood, take notes.

Cinema’s Evolution: A Continuation

As we close this chapter on early cinema, we realize that art imitates life—even if that life involves a lot of bleakness and ennui. The progression of Nottingham’s cinematic legacy reflects not only the struggles and joys of ordinary people but also a dash of irony that’s as rich as the lace they produce. And while we may not walk away with any grand insights about the meaning of life, at least we can chuckle at how the drudgery of work can lead to moments of pure, unfiltered cinematic magic. Perhaps the true joy is realizing that the same dusty lace factory can inspire multiple generations to roll their eyes and feel seen. Cheers to that!